Stephen Poloz is refusing to call it a recession, but the Bank of Canada Governor says the country needs another jolt of interest rate relief as the economy shrinks and exports stall.

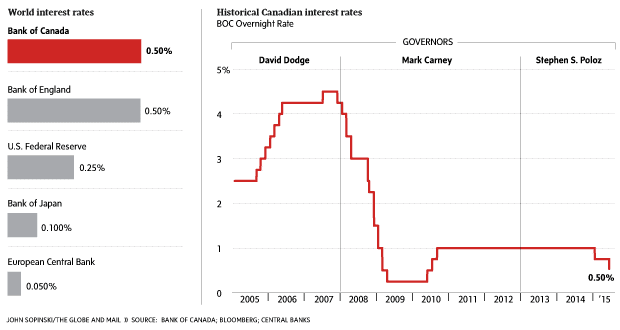

The central bank lowered its trend-setting overnight rate a quarter percentage point Wednesday to 0.50 per cent – the second rate cut in six months that sent the Canadian dollar tumbling and prompted three major banks to lower borrowing rates.

The central bank also slashed its forecast for the Canadian economy, acknowledging for the first time that gross domestic product will likely decline in both the first and second quarters. And the bank said growth for the full year will reach just 1.1 per cent, a major downgrade from the nearly 2 per cent it was predicting just three months ago.

Back-to-back quarters is the traditional litmus test of whether an economy is in recession. But Mr. Poloz said it will take months for experts to make that determination, carefully avoiding using the R-word.

“I’m not going to engage in the debate over what we actually call this,” Mr. Poloz told reporters in Ottawa. “No doubt, we have worked our way through a mild contraction.”

The Canadian dollar lost more than a cent to end at 77.40 cents (U.S.) in the wake of the decision – its lowest level since the depth of the recession in 2009. Toronto-Dominion Bank reacted with a reduction in its prime rate Wednesday by a 10th of a percentage point to 2.75 per cent and Royal Bank of Canada and Bank of Montreal reduced theirs by 0.15 points to 2.70 per cent from 2.85 per cent, effective July 16, 2015.

The Bank of Canada acknowledged that lower rates could exacerbate record household debt levels and add fuel to overheated housing markets in cities such as Toronto and Vancouver. But Mr. Poloz said it’s a risk worth taking given the shock facing the economy.

“Canada’s economy is undergoing a significant and complex adjustment,” the bank said in a statement accompanying its rate decision. “Additional monetary stimulus is required at this time to help return the economy to full capacity and inflation sustainably to target.”

The latest rate cut marks a sudden about-face by Mr. Poloz, who has repeatedly insisted that the economic hit from the oil price collapse would be quickly offset by surging non-oil exports, such as car parts, lumber and services. He had characterized his earlier January rate cut as “insurance.”

Six months later, the export rebound remains elusive, in spite of a much cheaper Canadian dollar. Mr. Poloz said the bank anticipated that cheaper crude prices would take a bite out of exports, but the failure of non-energy exports to pick up as the dollar falls is a “puzzle” that the bank is now hard at work trying to sort out.

Among other reasons for the rate cut, Mr. Poloz cited a deeper-than-expected plunge in Western Canadian oil patch investments and weaker growth in China, which is depressing other commodities, including metals.

“The facts have changed, quite quickly actually, in the last two to three months,” Mr. Poloz told reporters. “One of the big shocks in this outlook is the downgrade of investment intentions by the companies in the oil patch.”

There is another reason the Bank of Canada may want lower interest rates, economists say. A growing gap between rates in Canada and U.S., where the U.S. Federal Reserve is poised to start increasing its benchmark, could help push the Canadian dollar even lower in the coming months, making exports more competitive in foreign markets and encouraging Canadians to spend more of their cash at home.

Part of the puzzle why non-oil exports have been slow to react to the lower dollar is that currencies are just one of many factors that companies consider before making investments, pointed out Ben Homsy, a fixed-income analyst at Vancouver-based Leith Wheeler Investment Funds.

“Short-term weakness in a currency doesn’t always spur a manufacturing firm to build a plant here in Canada and to start employing people,” Mr. Homsy said. “You need a sustained period of currency weakness.”

Other experts speculated the bank may have opted to cut rates now, rather than waiting until its next scheduled announcement Sept. 9, to avoid being seen as meddling in the coming federal election.

Canada’s fundamental problem is that it now has a distinctly two-track economy – one faltering badly because it’s tied to oil and other commodities, and another growing modestly due to “solid” household spending and an improving U.S. economy.

A massive plunge in business investment – down 16 per cent in the first quarter – has become a deadweight on the economy. The energy sector makes up less than 20 per cent of the economy, but it drives an oversized share of business investment. The bank now says it expects investment in Canada’s oil patch to plummet close to 40 per cent this year, significantly worse than the 30 per cent it initially thought, as long-term investments in the oil sands are delayed or put on hold until the price of crude recovers.

OTTAWA — The Globe and Mail

Published Wednesday, Jul. 15, 2015